From The Record, Fall 2016

A Sustainable Dream

Eat Local. Eat Clean. Farm-to-Table. Go Green. A myriad of slogans that have entered the American vernacular in recent years points to a rising interest in food: the manner in which it is produced, the manner in which it is prepared, and the manner in which we consume it.

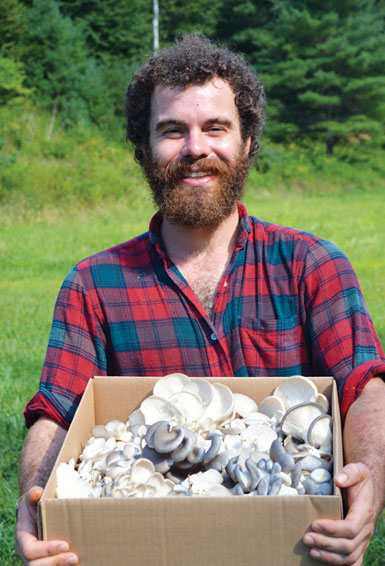

For almost a decade, Virginia native Matthew W. Reiss II '06 was at the confluence of farming, food, and culture in the Pacific Northwest, first studying sustainable agriculture in Olympia, Washington, then managing a farm on Bainbridge Island, ten miles from Seattle. Now Reiss and his partner Jenna Kuczynski have brought their passion and knowledge back to Southwest Virginia, fulfilling Reiss' dream of owning and operating a sustainable farm.

His enterprise is strongly influenced by the ideas of permaculture. Although difficult to define, at its core the permaculture movement applies natural ecological principles to human systems. A natural ecosystem sustains itself in a closed loop, providing its own energy, producing no waste, and relying on interdependence rather than independence. Common practices that embrace Permaculture include turning garden scraps into compost to amend the soil, or designing buildings to use existing resources like geothermal energy. The principles of Permaculture extend beyond agriculture and land use, though. Reiss says the three foundations of the movement are "care of the earth, care of people, and the wise use of resources," principles that can be applied to most human activity.

His enterprise is strongly influenced by the ideas of permaculture. Although difficult to define, at its core the permaculture movement applies natural ecological principles to human systems. A natural ecosystem sustains itself in a closed loop, providing its own energy, producing no waste, and relying on interdependence rather than independence. Common practices that embrace Permaculture include turning garden scraps into compost to amend the soil, or designing buildings to use existing resources like geothermal energy. The principles of Permaculture extend beyond agriculture and land use, though. Reiss says the three foundations of the movement are "care of the earth, care of people, and the wise use of resources," principles that can be applied to most human activity.

At Gnomeshead Hollow Farm and Forage, Reiss has designed his commercial farming operation to "close as many loops as possible." For example, he uses a readily available agricultural byproduct as a growing medium, or substrate, thereby closing the loop on another industry's waste. Reiss can use the sawdust created by local lumber mills as a substrate for two flowerings of mushroom, but what becomes of the waste after that? The mushrooms convert the sawdust into living mulch, which eventually becomes part of the soil's humus layer. The benefit of this system is both ecological and financial: the local, abundant, and cheap substrate helps make the 50-acre farm's mushroom operation profitable.

Reiss cultivates almost 10 mushroom varieties on the farm, from the well-known shiitake to the more unusual blue oyster and lion's mane. Using fans and a simple fog generator supplied by the farm's gravity-fed spring, Reiss' low-tech grow houses emulate a forest canopy. This passive growth set-up produces mushrooms closer in flavor to wild-grown than those cultivated under HVAC. Reiss admits that with their low-tech set-up, "we are at the whim of nature here. If it gets too hot or too cold, we're in trouble." In their third summer growing mushrooms in Virginia, however, they've managed to turn a profit without outside investment.

About half of the farm's business comes from selling mushrooms at farmers markets and to restaurants in Blacksburg, Roanoke, and Winston-Salem. The other half comes from Gnomestead Hollow's line of fermented vegetables (pictured above), which retails at natural food stores throughout the region. Gnomestead purchases excess produce from area farms-vegetables that might otherwise be discarded-and processes them into krauts and kimchees in a county-owned canning facility. In exchange, Reiss and Kuczynski teach classes at local schools on fermentation and tissue propagation. By taking advantage of existing resources in a mutually beneficial relationship, another loop is closed.

The life that Reiss and Kuczynski have chosen is difficult but rewarding. Their workdays average 10-15 hours, but Reiss say that at least once a week he finds himself pulling a 20-hour day. Asked how they manage such a schedule without burning out, Reiss answers, "It's work that we love to do, which makes all the difference."

The life that Reiss and Kuczynski have chosen is difficult but rewarding. Their workdays average 10-15 hours, but Reiss say that at least once a week he finds himself pulling a 20-hour day. Asked how they manage such a schedule without burning out, Reiss answers, "It's work that we love to do, which makes all the difference."

One may well question whether Reiss' study of economics at Hampden-Sydney is relevant to his current life as a farmer. Yet Reiss traces much of his passion for small, sustainable farming to the theories of free market and Austrian economics that he studied at H-SC. Reiss went on to study mycology in Washington state, but he is thankful that he had a broad liberal arts education before immersing himself in science. "The core liberal arts at Hampden-Sydney, especially the Rhetoric Program, gave me the foundation to be able to process information, which I have found invaluable. The classes challenged me to an extent I hadn't experienced before, but the way the professors presented the material was incredibly engaging. Studying the liberal arts is one of the best things I could have done for myself."

In fact, talk to Reiss for any length of time and the conversation may veer from Farm Bill amendments pending before Congress, to The Wealth of Nations by Scottish economist Adam Smith, to the Trivium of classical education-and he will connect each topic to his life on the farm. He is yet another example of that oft-used phrase, "You can do anything with a degree from Hampden-Sydney."