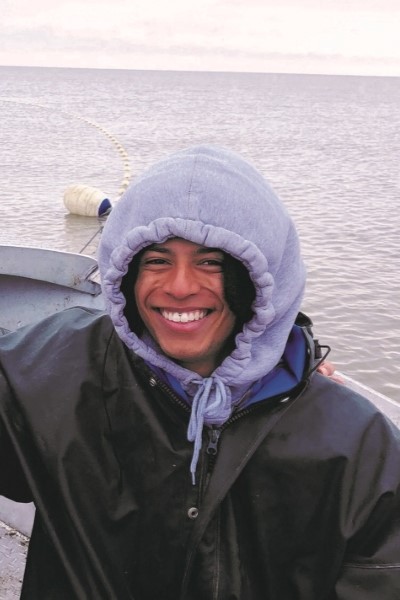

Izac Olatunji ’23 spent the summer of 2022 learning about the native plants of Quinhagak, Alaska, and the Native Alaskan tribe of the Yup’ik as a research assistant to Associate Professor of Rhetoric Sean Gleason. Dr. Gleason’s work in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta (Y-K Delta) encompasses the archaeological excavation and preservation of artifacts from Nunalleq—a circa 1600 Yup’ik village once preserved in ice that became endangered due to permafrost melt in 2009—and consulting on contemporary Yup’ik challenges such as infrastructure needs and search and rescue made more difficult due to climate change.

Izac assisted Dr. Gleason with configuration documentation of unmanned aerial vehicles, which the tribe and Dr. Gleason’s team use to support heritage and land management efforts. A biology and fine arts double major, Izac also studied Yup’ik ethnobotany and photographed the tribe members performing traditional subsistence activities like berry picking and fishing.

As someone of Yoruba Nigerian ethnicity, who grew up in England, and now lives in America, Izac was struck by the connection that the Yup’ik people, especially the youth, have with their ancestral traditions. He attributes at least some of this connection to the dig at Nunalleq that has unearthed over 100,000 artifacts, all of which reside in the Nunalleq Cultural and Heritage Center in Quinhagak.

“The younger generation is seeking out their ancestral cultural ways,” Izac explains. “In a sense, they’ve grown up alongside the cultural center, and they’ve been infused with a curiosity in where these artifacts are coming from.”

“It was almost indescribable experiencing this rich culture,” he says. “It was so much more than hearing a different language or eating different food. I was able to experience how the tribe connects their lives in a modern world to ancestral traditions of communal living, self-reliance through hunting and fishing, and cultural expression through drum circles and dancing.”

As an outsider to the Yup’iit and being cognizant of the danger of cultural appropriation, Izac was very intentional as to how he went about making inroads with the tribe. He learned to fish and forage for his own food, endured the intensity of a maqii steam bath, and participated in communal living, which is a foundational element of Yup’ik life. Being willing to experience a bit of Yup’ik yuyuraq—the way we live—Izac built trust with a few of the younger members of the tribe, who in turn introduced him to other members.

“Teyana and her friends and family would take me out ATV riding around the beach and the village. They showed me different berry picking areas and types of berries like salmon-, black-, and blueberries,” Izac says.

“I had never fished before I went to Alaska,” he continues. “I didn’t even really eat fish, but it is almost necessary in Alaska due to the difficulty of getting groceries in such a remote location.” Izac was a fast learner, earning a Yup’ik nickname from Warren, one of the tribe’s elders: tengualria, which means flying fish.

As he experienced the rigors of life in the Y-K Delta, Izac remained mindful of his job as a researcher, recording his time with the Yup’ik through field journals and photographs—taking care to document, but not consume. “Documenting ethnobotanical and anthropological subjects is very scientific,” he says. “But while you have to be careful about romanticizing the subject or imposing your own Western infliction on the subject, there is also an art to it. There’s a way to use light and shape and composition all together to create not only a piece of documentation but also a beautiful image.”

“I wanted to be able to return the photos back to the people I had been taking photos of very quickly,” he continues. “The transactional relationship between myself and the people I met and who were gracious enough to take me fishing and allow me to photograph them was important to me. I had to get creative due to technical challenges like slow or non-existent internet, limited access to computers or smart phones, but I didn’t just want to take photos and then leave. That’s just another form of colonialism that I wasn’t interested in participating in.”

After being mindful of limiting his impact on the Yup’ik throughout his time with the tribe, Izac had a surreal moment during a stopover in Chicago on his way home from Alaska. “I went to the Field Museum, and there was an exhibit on Native Alaskan tribes including the Yup’ik. It felt very distorted because I felt those artifacts should be with the people that own them culturally,” Izac says. “While they may be harder to see or access somewhere like the Y-K Delta, the artifacts are not meant for the general public at the expense of the cultures they come from.”

Back on the Hill during his senior year, Izac translated his research in Alaska into a year-long Honors distinction project studying the birchwood fungus and its use in punk ash, which is a stimulant used both recreationally and culturally in Yup’ik communities. Izac also exhibited some of his photographs in the Gallery as his fine arts capstone project in late spring, even setting up a live stream link to share with the village to continue showing his appreciation to the people who opened their homes and lives to him.

Dr. Gleason states that Izac’s experience is thanks to Hampden-Sydney’s small class sizes that encourage relationship- and opportunity building between faculty and students and the College’s focus on student research. What Izac gleaned from this experience, however, is a testament to his thoughtfulness about his role as a global citizen and his ability to make meaningful connections—traits that will serve Izac well long after graduation.